Listen at this link:

Air Date: Week of April 20, 2012

stream/download this segment as an MP3 file

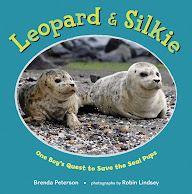

Silkie. (Photo: Robin Lindsey)

|

Alki Beach is a popular destination for Seattle natives, and it’s also home to some of the region’s seal population. Seal pups are left alone on shore while their mothers search the sea for food, and curious people and dogs endanger the young seals. But a group of concerned neighbors called Seal Sitters have banded together to protect the pups and educate people. Seal Sitter founder Brenda Peterson, author of the children’s book “Leopard and Silkie” and 11 year old volunteer Etienne, spoke with host Bruce Gellerman about their quest to save seal pups.

Transcript

GELLERMAN: It's Living on Earth, I'm Bruce Gellerman.

[SOUND OF CROWDS ON ALKI BEACH]

GELLERMAN: A small crowd gathers on Seattle’s Alki Beach. Nearby, a seal pup lies in the sand.

[LITTLE GIRL: Can we go say hi to him Daddy?]

GELLERMAN: Like other mammals, seal pups depend on their moms for food. But while she takes to the sea in search of fish, the pup is left to survive the perils of the shore alone.

That is where Brenda Peterson comes in. She finds and saves seal pups by Seattle’s Salish Seashore. Brenda Peterson is the founder of Seal Sitters and the author of the new children’s book “Leopard and Silkie.” It’s about rescuing seal pups. Brenda Peterson, welcome to Living on Earth.

PETERSON: Thank you, Bruce. Good to be here.

GELLERMAN: So, these marine mammals are protected by the Marine Mammal [Protection] Act. The federal government protects them, but you say that they’re being threatened.

PETERSON: I think they are needing more protection and it’s because our beaches are really urban at this point. And, though these are urban seals, the pups are not prepared for such activity.

The moms leave the pups after just a few hours sometimes. But when you’re on Alki beach in Seattle, there is so much activity that the mother who leaves the pup at say, 4:00 am when it’s very peaceful, will try to come back to pick up the pup after fishing to nurse the pup, and there are five hundred people on the beach. And if it’s so full of people, their survival goes down.

GELLERMAN: So, basically leave the pups alone!

PETERSON: Yes. The shoreline is a very important place. They spend fifty percent of their time onshore. So we’ve been trained for the past several years by NOAA for marine mammal strandings to look to see if there’s human caused injury, to see if there is a pup on the beach who is injured or starving or not surviving the weaning period. And when we go out on our daily walks, instead of tuning out, we’ve trained people to keep their eyes out for pups.

GELLERMAN: So, this organization that you’ve founded Seal Sitters, basically trains people to help keep pups separated from people.

Etienne and her sister Noemi at Alki Beach. (Photo: Robin Lindsey)

PETERSON: Exactly. The number one predator on the beach is dogs off leash. There are diseases that go back and forth between all of the pups. So we try to protect our own domesticated pups as well as the seal pups. So we saw a need to actually do a kind of daycare on the beach for newborn pups.

GELLERMAN: In your new book “Leopard and Silkie,” about two seal pups, you use a word which I had never come across, it’s ‘allomothering.’ Do I have that correct?

PETERSON: I was hoping you would ask about that.

GELLERMAN: (Laughs.) Well, what’s allomothering?

PETERSON: I came upon this idea that scientists call allomothering, which means nurturing a species that is not your own.

GELLERMAN: So, the people, the volunteers that you train in seal stitting, are allomothers!

PETERSON: They are allomothers and allofathers. We have guys on the beach, we have teenagers, we have grandmothers we have retired people. I call it neighborhood naturalists.

GELLERMAN: I understand that you have one of your young volunteers there: Etienne, are you there?

ETIENNE: Yes.

GELLERMAN: Hi, so you are how old are you, Etienne?

ETIENNE: I just turned eleven.

GELLERMAN: How long have you been doing seal sitting?

ETIENNE: Well, I really started when I was in second grade. The first time I saw a seal pup it was Forté, we named him Forté because he was strong and he had been injured. My family came down to see this pup and when we did we saw Robin Lindsay, a photographer and she told us all about the seal and seal sitters.

Leopard. (Photo: Robin Lindsey)

GELLERMAN: Wow!

ETIENNE: A bit later, in second grade, we were doing a project of people who stick their necks out and volunteer to help to make our world better. I decided to do Robin. Ever since then I was part of the Seal Sitters.

GELLERMAN: So you gave a name to one pup, any others?

ETIENNE: I haven’t named one. But there have been some named Pa and Queen Latifah. There’s one named E.T…

GELLERMAN: Have you ever saved a seal pup?

ETIENNE: I haven’t personally. But I have helped to save one by telling people about them and not to hurt them or go near them, don’t disturb them.

GELLERMAN: So, if I was walking down the beach and I had my dog off leash, what would you say to me?

ETIENNE: I would ask you to please put your dog on a leash, so your dog can’t get injured by the seal. Also, his scent could rub off onto the seal, as a human’s could, and then the mother would not have her scent on her pup and then she wouldn’t come back to get him.

GELLERMAN: Oh, really? Has that happened? Have you ever sent that happen?

ETIENNE: I have never seen that happen. But it has happened before. People have poked them with sticks, even gone as far to take them into their bathtubs. Sometimes, they die.

GELLERMAN: You know, Etienne, I’m looking at this book by Brenda, and I’m looking at the pictures and seals are really cute.

ETIENNE: Yes they are!

GELLERMAN: But, would you spend so much of your time and emotional energy saving an animal if it were ugly?

ETIENNE: Well, I would because they’re still an animal. And they’re still a life and they’re still part of our planet.

GELLERMAN: At your age, many kids are thinking about doing babysitting, not seal sitting. Do you think you’re going to get busier with your life and you’re going to stop doing this?

ETIENNE: Well, I am busy right now, but I still try my hardest to be able to do this, too. I want to try to be a seal sitter for as long as I can.

GELLERMAN: What do you think of Brenda’s book, “Leopard and Silkie?”

ETIENNE: I love the book. It’s a great book. It shows how you can help a seal.

GELLERMAN: Well, Brenda, that’s high praise from Etienne!

PETERSON: Out of the mouth of babes. I am so moved whenever I hear the children because they are the future.

GELLERMAN: Well, Brenda, what’s the future of federal funding to save marine mammals? I know the funding is scheduled to be zeroed out.

PETERSON: We’re really alarmed about that, Bruce, because stranding networks such as ours, they are the first responders to anything on the beach that washes up or is stranded. So the stranding networks are the kind of vital resource that shows us the health of our marine systems. And why should we cut funding to the only thing where humans and animals interact successfully and compassionately?

GELLERMAN: Well, Brenda, thank you very much.

PETERSON: Thank you, Bruce.

GELLERMAN: And, Etienne, thank you.

ETIENNE: Thank you for having me.

GELLERMAN: Etienne is a volunteer seal sitter. The organization, based in Seattle, was founded by Brenda Peterson, who’s also author of the new children's book about saving seal pups “Leopard and Silkie.”

Links

Mermaid award ceremony, Merpalooza, Orlando, Florida

Mermaid award ceremony, Merpalooza, Orlando, Florida Mermaid Enaikai with her lovely tail flukes

Mermaid Enaikai with her lovely tail flukes Brenda interviews a professional mermaid

Brenda interviews a professional mermaid